The African continent has recently seen an explosion of foreign investment in its start-up space. As different ecosystems around the continent continue to develop and trade, continue to grow, African start-ups continue to be attractive businesses to investors. Between 2019 to the first quarter of 2022, the continent recorded an excess of 4Billion dollars according to data tracked by Africa: The BIG DEAL. It is further estimated that the continent might record almost 8 billion dollars in start-up funding by the close of 2022, with more than 1 billion dollars already raised.

As African start-ups continue to impress investors, other ecosystems still dominate the fundraising space. In 2021, start-ups in South East Asia raised at least 21 Billion dollars according to SE Asia deal review, in Europe start-ups were expected to raise an excess of 100 billion dollars by the end of 2021 and start-ups in North America start-ups raised an excess of 300 billion dollars.

Data shows that while the African continent continues to celebrate the massive growth in investment in start-ups, it is still a far cry from the global competitive scale.

So why are we happy?

We are happy because entrepreneurs in Africa find it harder to raise investment compared to entrepreneurs in other parts of the world. With the many structural barriers squarely based on market dynamics (advancement in policies, infrastructure etc.), it is a truly remarkable feat for any African focus company to attract investment in the millions of dollars. The underlying conversation, becomes, that as more start-ups gain access to funding, the ecosystem becomes more attractive to more established VCs. From a broader macro-economic perspective, start-ups are now in a better place to provide job opportunities for the ever-increasing talent in the continent.

Irrespective of how much money start-ups in the continent have raised so far, data from different deal-trackers, have an underlying resemblance of biases captured. But one bias seems to become more predominant, and that is that; most of the money being raised in the continent goes to founders who have some form of education in Europe and America.

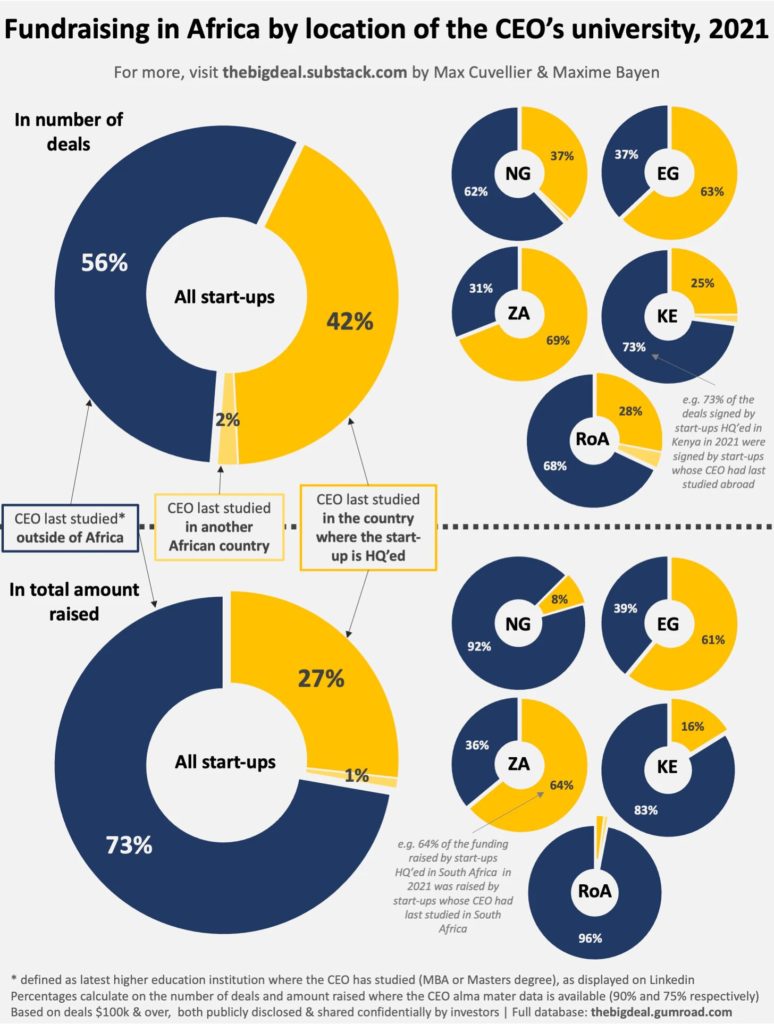

Here, let us look at this analysis by Max Cuvellier from Africa: The BIG DEAL

In 2021, 56% of all deals were secured by founders who have studied overseas, and only 44% were secured by founders who studied on the continent. Furthermore, founders who have recently studied in Africa account for only 27% of all deal value amounts, whereas 73% of the funds have gone to founders who have studied overseas. What this means, is that founders, who have recently studied on the continent find it harder to raise funds than founders that have studied overseas.

Is this something to overlook? well, as the writer researched to write this article, he reached out to VCs, Angels etc. operational in the continent with a need to discuss his findings. However, it was clear that the business case has little to do with the investment. One VC argues that investors sometimes consider the network of the founder, as an extension of their ability to raise money at a higher valuation.

So, the question then is, how do investors value the team? does one’s ability to lead, inspire and grow a business dependent on where they studied and their social network? Is it not part of the investors’ responsibility to introduce the founder to the right people? What does this mean for the many amazing founders who have not studied in Europe and North America? Where does the exit go? And what is the growing impact on the data? The writer hopes the reader can figure out answers to these questions.

The writer is not oblivious of the fact that the argument of the individual’s ability to lead can be in some form associated with their experiences (including but not limited to professional and academic). But one thing that stands out, is that, unlike other ecosystems, Africa seems to be the only continent where the founder’s school is a determinant in fundraising.

The writer also understands that some schools, can provide access to a dynamic array of funding options through its alumni or associated organisations; this may be particularly true for schools like Stanford, Harvard, Oxford etc. But the truth is, founders in Africa irrespective of their professional background or expertise, and the socio-economic viability of their business still find it harder to access investment because of the schools they attended.

So, what then? While there are many biases, fund managers, just for their own sake, think beyond social networks, and must base their decisions on the team’s ability to deliver on the business case rather than what school they attend.

Unless otherwise, it is a deliberate funding strategy of VCs to rank a team’s ability to build a thriving business based on the school they attend, it makes no investment sense to do so. If this is merely an oversight or a bias that has not been given attention, then it is time to think more seriously about it. Is the writer saying founders that attended these schools are incompetent? God forbid, but rather the writer’s argument is primarily on the implication this bias can have in the long run.